As Americans embrace Ethiopian cuisine, its farmers grow more teff

By ,

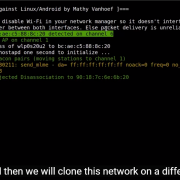

It’s almost midnight, but Zelalem Injera, an Ethiopian bread factory housed in a cavelike Northeast Washington warehouse, is wide awake. As its 30-foot-long injera machine hums, Ethiopian American businessman Kassahun Maru, 61, proudly explains that it cranks out 1,000 of the fermented Frisbee-shaped discs every hour for the region’s growing number of ethnic grocery stores, health food boutiques and Ethiopian restaurants.

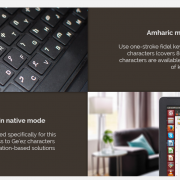

Injera — the Ethiopian staple food that doubles as cutlery — is made from teff, a tiny grain ubiquitous in the Horn of Africa and until recently almost unknown elsewhere. But the teff that Zelalem Injera uses is grown in America. The 25-pound sacks stacked along the wall read “Maskal Teff: An Ancient African Grain. Made in Idaho.” Once solely grown in the rugged Ethiopian highlands, teff is popping up in the windswept fields of the American heartland.

Waves of immigrants come to this country seeking a taste of home, but in doing so they change our tastes, too. Increasingly, cuisine can be a sort of international connective tissue, with people who may never travel to, say, India, now able to choose from five brands of naan in the ethnic foods aisle at Wegmans. The demand for teff has created a ripple effect that reaches from Addis Ababa to Boise to D.C.

When the first waves of Ethiopians began arriving in Washington after the 1974 Marxist coup, they had so few of the necessary supplies at hand that they made injera with Aunt Jemima pancake batter. “It tasted funny,” recalls Getachew Zewdie, 47, the owner of Dukem, one of U Street’s first Ethiopian restaurants.

“There was just so much demand for real injera,” Zewdie says, standing amid sizzling skillets and bubbling vats of pungent yellow lentils and strips of meat tibs drizzled in rosemary sprigs and garlic. While injera is imported every day on Ethiopian Airlines, it’s not as popular as the freshly made kind. The region’s injera industry — it’s baked at more than 50 locations in and around Washington — earns about $12 million a year with an estimated 4,000 packs sold per day, Maru estimates. Today, Zewdie buys his injera from Maru, and Maru buys his teff from the Teff Company in Caldwell, Idaho.

A growing market

A combination of factors has spurred the growth of the U.S. teff market. One is scarcity: The Ethiopian government routinely bans its export to protect prices from rising inside the country during lean seasons. Another is a shift in American dietary habits. The rise in Ethiopian immigrants and the concomitant rise in the popularity of Ethiopian food have increased demand, as has the surge in vegetarianism (a two-ounce serving of teff has as much protein as an extra-large egg). Yet another is the increased awareness of gluten allergies; gluten-free teff is a welcome alternative to wheat.

“It is a great crop,” says Don Miller, a plant breeder who works with teff at a seed research facility in West Salem, Wis. “And its uses are expanding all the time.”

A native of Texas, Miller, 60, sports a mustache and wears an array of turquoise rings. He has a PhD in agronomy and studies the use of teff as forage for horses and other animals. He received USDA grants in 2009 to 2010 to promote the African grain. “Maybe the Ethiopians like the taste a little more than I do,” he concedes, “but, you know, I really like it as a gluten-free chocolate cake.”

Teff — which looks like wispy green wheat — is also being grown in Nevada, California and Texas, Miller says . “It’s just a really exciting time for teff.”

Read more